At the heart of the motorised tricycle developed by De Dion Bouton was a frame that had initially been designed for pedal-powered machines. The earliest machines had the so-called ‘swan neck’ frame, based on the pedal- powered tricycles manufactured by Humber, Rudge, Quadrant, and others in the early 1890s. The arrangement of the engine, ignition system, fuel storage and battery can be entirely attributed to De Dion Bouton.

Given the disproportionate rear weight balance of a tricycle, the weight of the principal components there is a matter of paramount importance. Most of the weight comes from the engine, and the De Dion Bouton unit was light and powerful, well designed, and accessible. It confounded other designers at the time who could not readily understand, and would not immediately accept, that this modestly sized design that developed 0.5hp did so at the unprecedentedly high speed of 1500rpm, and was reliable, when other engines barely reached 1000rpm. This achievement was possible because of the quality and lightness of the internal engine components, which combined to produce relatively modest inertial and impulse forces in operation. The fundamental design of the engine served De Dion Bouton well in that, apart from the availability from 1900 of a water-cooled head and a steady growth in capacity and power output, it remained largely unchanged in its basic design until the last Type AL left the factory in 1909.

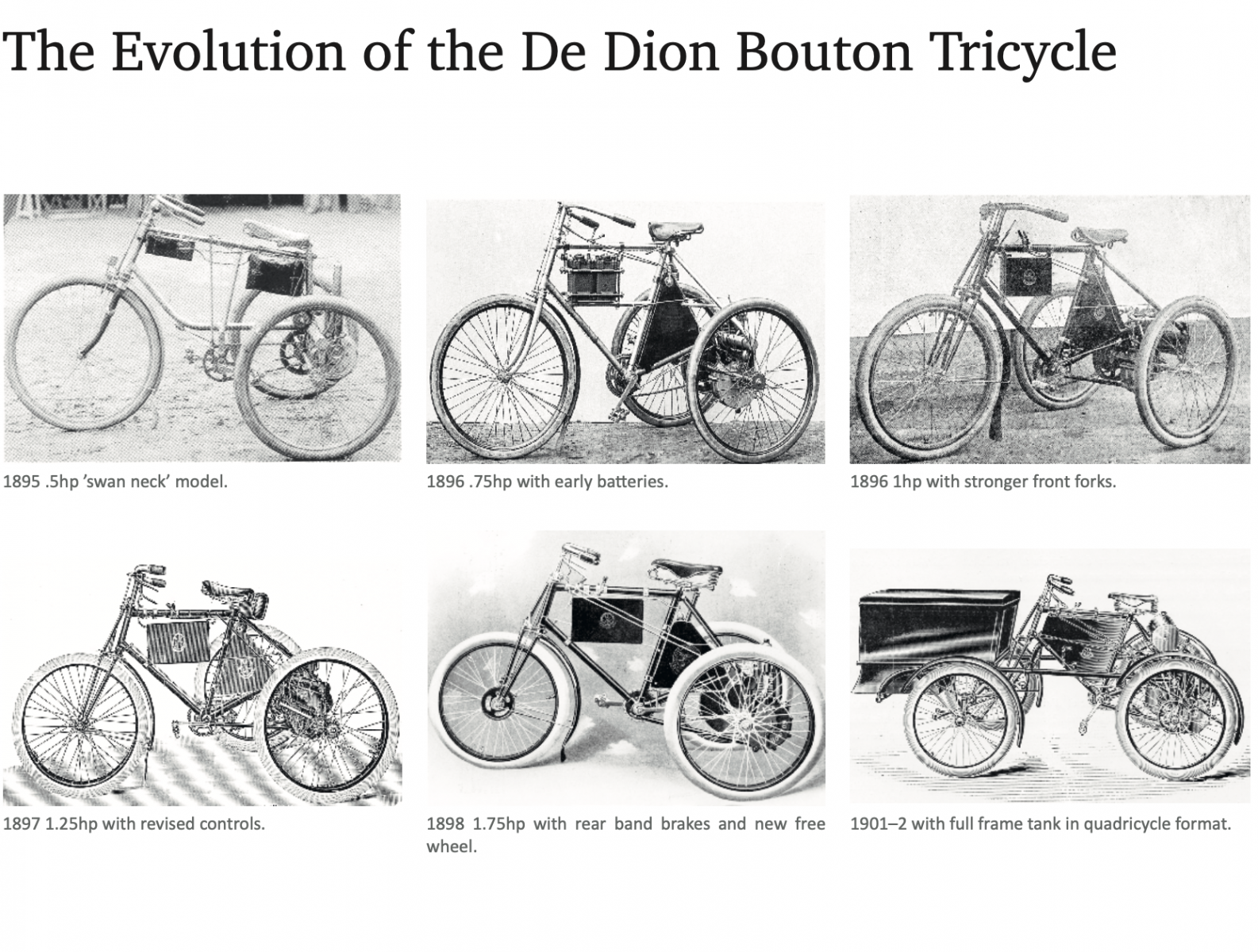

Between December 1895, when the De Dion Bouton half horsepower engine was first used, and April 1896 when the larger .75hp engine arrived, there were numerous changes to the tricycles, and each published photograph is different from the others in some respect. Some publications state that De Dion Bouton experimented with hot tube ignition, but the author has not located any photographs reflecting this. The ignition was electric from the start; initially, the coil was mounted below the crossbar near the headstock, with the accumulators beneath the saddle, and then the accumulators were positioned adjacent to the headstock, possibly for reasons of improved overall balance. The cylindrical petrol tank sat on top of the bridge axle, below the level of the cylinder head, and a hand pump was attached to the underside of the handlebars to pressurise the tank. The main motor pinion transmitted power through a toothed motor drive wheel to the rear wheels. Braking was through a plunger brake operating on the front wheel, and a leather-lined band on the rear drum attached to the motor drive wheel. There was no free wheel arrangement, and so all models had a vertical lever that descended from the crossbar to the pedal crank, for the sole purpose of disengaging the pedal crank once the engine was in operation. There was an early version of a surface carburettor that rested on the horizontal frame tube.

The 1896 tricycle was radically different from its predecessors, but entirely consistent again with the contemporary pedal-powered examples. In most respects it established the visual and functional blueprint for the machines that succeeded it: the widely used three-wheel pedal cycle frame had been adapted, and still incorporated the earlier bridge axle. This axle is a characteristic feature of the De Dion Bouton tricycle. Since Clément, along with Decauville, produced the early frames, it is perfectly possible that this element was initially one of their designs. Decauville had wide experience in the production of heavy rail machinery by this time. Following a fire in the Decauville factory, Clément became the sole supplier of frames that De Dion Bouton used in its tricycles. A triangular-shaped surface carburettor was placed beneath the rider’s seat and clamped to the rear frame, with the fuel outlet on the nearside casing; there were two crossbar-mounted controls, one for adjusting the ‘rich’ and ‘lean’ setting, and the other the throttle. There was electric ignition, and a cam control timing adjustment was possible through a lever positioned on the saddle post. The engine launched in April 1896 had a larger bore than the 1895 version, producing an output of .75hp. The pedal sprocket was of more substantial construction and included the free wheel arrangement that continued with all models. The front plunger and differential brakes were also used.

On one surviving illustration, there is an additional horizontal tube to support the weight of the batteries and a decompression control was installed on the nearside of the frame and attached to the same lower crossbar. It is unclear whether this frame layout was a prototype or whether it entered full production in 1896.

In September 1896, further upgrades were introduced that were intended to deliver more speed, and produce a more robust, safer vehicle. The power output of the engine rose by 33 per cent to 1hp at the expense of only half a kilogram of extra weight. The heavy batteries were abandoned in favour of lighter, more efficient batteries. A bracing rod was fixed between the base of the pedal sprocket and the lower offside of the engine, and the simple bicycle-style front forks were replaced by the altogether more purposeful looking four-tube arrangement that was to be the most readily recognisable characteristic of a De Dion Bouton tricycle. The front plunger brake was still in place, operated by an offside brake lever attached to the handlebars, but the rear band brake was now activated by a brake lever that pivoted from a fitting on the nearside of the headstock. The company had learned much from the usage of its machines in French road racing.

In January 1897, there was a further 25 per cent increase in power available from the new 1.25hp engine, whose bore had been increased to 62mm. In relation to the substantial changes made to the tricycles over the previous two years, the 1897 model received relatively few upgrades, and they were cosmetic. The headstock-mounted rear brake lever had been replaced with a more conventional lever descending from the handlebar; the previous practice of removing one hand from the handlebar to operate the rear brake must have challenged the nerves of some less experienced riders when travelling at speed. The linkages of the throttle and mixture controls now ran flush with the crossbar before descending from pivots to the air valve of the surface carburettor rather than running diagonally to the valve. The battery box was more substantial in size. The rear shafts were increased in diameter from 17.5mm to 19.5mm.

January 1898 witnessed an increase in output to 1.75hp from essentially the same engine that had been designed more than three years previously. There was a transition from a bolted inlet valve to a bell-head inlet valve during the year. The changes from the 1897 model included the installation of a front band brake to replace the previous plunger brake; this entailed a revision to the front forks’ design, and two lugs were attached to the forward nearside support to hold the brake band itself as well as the pivot mechanism. The three control levers were clustered at the front of the crossbar for ease of access; previously the ignition cam had been adjusted by a lever beneath the saddle. The design of the free wheel on the pedal sprocket changed so that the open fretwork layout was succeeded by a more compact arrangement. The same number of pawls were set into the mechanism, but the central toothed wheel had been replaced with a toothed perimeter. The rear half shafts were now enclosed in metal sheaths measuring 45mm in diameter.

The 1.75hp engine launched in January 1898 was not superseded by the 2.25hp engine until June 1899, making this capacity unit one of the longest-lived tricycle engines. At the same time, its production coincided with the period of highest demand for tricycles, ensuring that there are more extant machines of this period with these engines than any other. During the period from January 1898 until the time when more powerful tricycles became available, and ultimately their appeal began to wane, several innovations and accessories appeared on the market, including spray carburettors from various manufacturers (including Claudel and Longuemare, as well as De Dion Bouton), gearboxes, oil and fuel tanks, and water tanks and radiators to accompany water-cooled engines.

The 2.25hp engined tricycle was launched in June 1899. The 29 per cent increase in power output over the 1.75hp engine came from a 12.5 per cent increase in capacity and 10.6 per cent increase in engine weight. The external measurements of this engine are identical to the 1.75hp power unit, making it difficult to distinguish between the two. The engine’s arrival was designed to provide De Dion Bouton with a competitive edge and offer flexibility with the heavier quadricycle; it was superseded within eight months by an even larger engine. This tricycle had a 104-tooth motor drive wheel and a 13-tooth motor drive, a surface carburettor, a front band brake and the usual differential braking mechanism.

At the beginning of 1900 there were two tricycles available: the 2.25hp air-cooled machine, and a new 2.75hp air-cooled tricycle that had only received Type Approval in February. This larger-engined tricycle had a 102-tooth motor drive wheel and a 16-tooth motor drive, a band brake on the front wheel as well as a brake on the differential. It retained the conventional surface carburettor in standard offering. Priced at only five guineas more than the 2.25hp model for Britain, it was positioned to appeal to the market. The water-cooled 2.75hp tricycle (sometimes referred to as the Type F) was available from May 1900. It had the De Dion Bouton spray carburettor, a combined oil/fuel/water tank behind the saddle, and the same braking arrangements as the earlier 2.75hp model. Later machines had full frame fuel tanks.